Imagine taking more painkillers to ease your pain-only to feel it get worse. It sounds backwards, but it’s real. This isn’t a mistake or a sign your condition is getting worse. It’s opioid-induced hyperalgesia-a paradoxical reaction where the very drugs meant to block pain end up making your nervous system more sensitive to it.

What Exactly Is Opioid-Induced Hyperalgesia?

Opioid-induced hyperalgesia, or OIH, happens when long-term opioid use causes your body to become more, not less, sensitive to pain. You might notice your original pain site starts hurting more, but now you’re also feeling pain in places that never hurt before-like a light touch from clothing or a breeze on your skin becoming painful. This isn’t tolerance. Tolerance means you need higher doses to get the same pain relief. OIH means the pain itself is growing, even as you take more drugs.

First seen in animal studies back in 1971, researchers noticed rats given repeated morphine injections became more sensitive to heat and pressure. Since then, human studies have confirmed the same thing: people on long-term opioids-especially high doses of morphine, hydromorphone, or fentanyl-can develop this condition. It’s not rare. While estimates vary, clinical reports suggest 2 to 10% of patients on chronic opioid therapy develop OIH. In palliative care and post-surgical settings, the numbers may be even higher.

How Is It Different From Tolerance?

This is where confusion sets in. Most people think if opioids stop working, it’s just tolerance. But OIH is different. With tolerance, your pain stays in the same place-you just need more medicine to control it. With OIH, the pain spreads. It becomes diffuse. It moves beyond the original injury or condition. You might have had lower back pain from a herniated disc, but now your legs, arms, and even your scalp hurt when touched. That’s a red flag.

Another clue? Allodynia. That’s when something that shouldn’t hurt-like a cotton sheet or a gentle pat on the shoulder-suddenly feels sharp or burning. This isn’t normal. It’s a sign your nervous system is stuck in overdrive. The same thing happens with hyperalgesia: a pinprick that used to feel like a light poke now feels like a needle. These aren’t psychological. They’re physical changes in your spinal cord and brain.

Why Does This Happen?

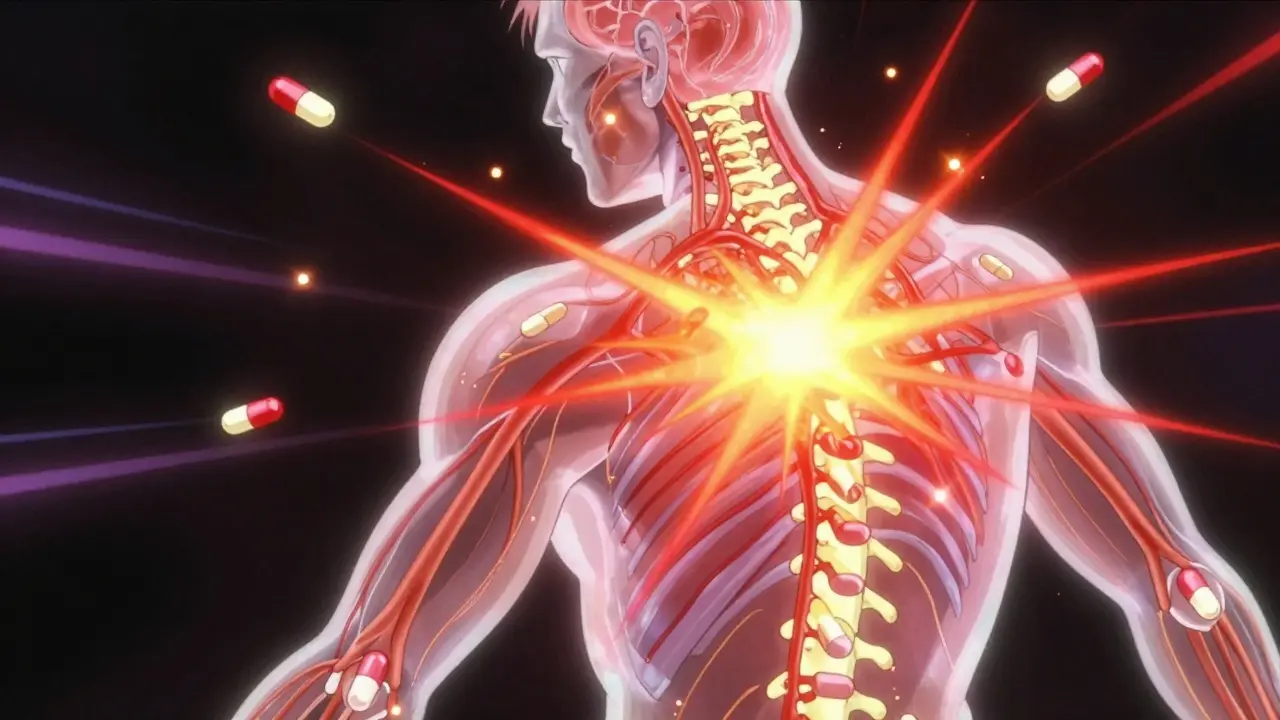

Your body doesn’t just shut down pain signals when you take opioids-it rewires how it processes them. Here’s what’s happening inside:

- NMDA receptors wake up. Opioids trigger a chain reaction that activates NMDA receptors in your spinal cord. These receptors are normally quiet, but when turned on, they amplify pain signals instead of blocking them. Think of them like a volume knob stuck on max.

- Dynorphin floods the system. Your body releases this natural peptide that actually increases pain sensitivity. It’s like your body is fighting back against the opioid, making you more reactive to pain.

- Descending pain pathways flip. Normally, your brain sends signals down the spine to calm pain. In OIH, those signals start screaming louder instead.

- Metabolites pile up. If you have kidney problems, your body can’t clear opioid breakdown products like morphine-3-glucuronide. These leftovers act like tiny irritants in your nervous system, making everything worse.

- Your genes matter. Some people have a variation in the COMT gene that makes them break down dopamine and norepinephrine slower. This leads to higher pain sensitivity overall-and a higher risk of OIH.

These changes don’t happen overnight. They build up over weeks or months of regular opioid use. That’s why OIH is rarely seen in people taking opioids for a few days after surgery. It’s a long-term problem.

Who’s at Risk?

Not everyone on opioids gets OIH, but some groups are more vulnerable:

- People on high-dose, long-term therapy (especially over 3 months)

- Those using injectable or intravenous opioids

- Patients with kidney disease (due to metabolite buildup)

- Individuals with a history of chronic pain conditions like fibromyalgia or neuropathy

- People with low-activity COMT gene variants

It’s also more common in people who’ve had multiple surgeries or are on opioids for non-cancer pain, like chronic back or joint pain. In cancer care, OIH is often missed because doctors assume worsening pain means the disease is progressing. But if the pain is spreading and becoming more sensitive to touch, OIH needs to be ruled out.

How Do Doctors Diagnose It?

There’s no blood test or scan for OIH. Diagnosis is all about pattern recognition. Doctors look for:

- Pain that worsens despite increasing opioid doses

- Pain spreading beyond the original area

- Signs of allodynia or heightened pain response to non-painful stimuli

- No new injury, tumor, or infection to explain the change

It’s tricky because OIH looks a lot like withdrawal, disease progression, or even depression-related pain amplification. That’s why many doctors miss it. A 2020 survey found only 35% of pain specialists felt confident diagnosing OIH. If you’ve been on opioids for more than 6 months and your pain is getting worse, ask your doctor if OIH could be the cause.

What Can Be Done?

Stopping opioids cold turkey won’t help-and can make things worse. The goal is to reset your nervous system. Here’s what actually works:

- Reduce the dose slowly. This sounds counterintuitive, but lowering the opioid amount often reduces pain over time. Your nervous system needs to calm down.

- Switch to methadone. Methadone is unique-it blocks NMDA receptors like ketamine does, while still acting as an opioid. Many patients see big improvements after switching. One study showed a 40% drop in post-op painkiller needs after using methadone.

- Add NMDA blockers. Low-dose ketamine infusions (0.1-0.5 mg/kg/hour) or oral magnesium sulfate can quiet the overactive pain pathways. These aren’t magic pills, but they help break the cycle.

- Use gabapentin or pregabalin. These drugs calm overexcited nerves by targeting calcium channels. Doses range from 900-3600 mg/day for gabapentin, or 150-600 mg/day for pregabalin. They’re not opioids, so they don’t worsen OIH.

- Try non-drug therapies. Cognitive behavioral therapy helps retrain how your brain responds to pain. Physical therapy can rebuild movement without triggering hypersensitivity. Both support recovery.

Some patients need a combination of these. One patient in Sydney, on high-dose oxycodone for 18 months with worsening back and leg pain, saw her pain drop 60% after switching to methadone and adding pregabalin. She didn’t need opioids anymore after 6 months.

Why Is This Still Controversial?

Some experts argue OIH is overdiagnosed. They say patients who seem to have it are really just experiencing uncontrolled pain or psychological distress. But the science is clear: animal studies show it’s real, and human studies confirm it. The debate isn’t whether it exists-it’s how often it happens and how to spot it reliably.

Dr. Stephan Schug, a leading pain specialist in Sydney, says the real issue is that OIH is taught poorly in medical schools. Most doctors learn about tolerance but never get trained to recognize the signs of hyperalgesia. That’s why patients suffer for months before getting the right help.

What Should You Do If You Suspect OIH?

If you’re on opioids and your pain is getting worse:

- Don’t increase your dose without talking to your doctor.

- Write down where the pain is, how it feels, and what makes it worse.

- Ask specifically: “Could this be opioid-induced hyperalgesia?”

- Request a review of your opioid dose and consider alternatives.

- Don’t stop opioids suddenly-work with your provider on a safe taper.

OIH isn’t a failure. It’s a biological response to a powerful drug. Recognizing it early can prevent dangerous dose escalations and help you find better, safer ways to manage pain.

Future Directions

Researchers are working on better ways to predict who’s at risk. Blood tests for biomarkers, genetic screening for COMT variants, and wearable sensors that track pain sensitivity are all in early trials. New drugs targeting kappa-opioid receptors show promise-these may relieve pain without triggering hyperalgesia at all.

For now, the best tool is awareness. If you’re on long-term opioids and pain is getting worse, it’s not just in your head. It’s in your nerves. And there’s a way out.

Is opioid-induced hyperalgesia the same as opioid tolerance?

No. Tolerance means you need higher doses to get the same pain relief, but your pain stays in the same place. OIH means your pain is actually getting worse and spreading to new areas, even as you take more opioids. The body becomes more sensitive to pain, not less.

Can opioid-induced hyperalgesia happen after short-term opioid use?

It’s rare. OIH typically develops after weeks or months of regular opioid use. It’s uncommon in people taking opioids for just a few days after surgery. The risk increases significantly with doses over 100 mg morphine equivalent per day and use lasting longer than 3 months.

What are the signs of opioid-induced hyperalgesia?

Key signs include: pain worsening despite higher opioid doses, pain spreading beyond the original site, allodynia (pain from light touch), and heightened response to stimuli like heat or pressure. You might also feel pain in areas that never hurt before, like your arms or scalp.

Can I stop opioids on my own if I think I have OIH?

No. Stopping opioids suddenly can cause severe withdrawal and make pain worse. Always work with your doctor to develop a slow, supervised taper. In some cases, switching to methadone or adding medications like gabapentin can help reduce dependence while managing pain.

Are there medications that treat opioid-induced hyperalgesia?

Yes. Methadone is often used because it blocks NMDA receptors. Low-dose ketamine, magnesium sulfate, gabapentin, and pregabalin also help by calming overactive pain pathways. These are not opioids and don’t worsen OIH. They’re used alongside a gradual opioid reduction.

How common is opioid-induced hyperalgesia?

Estimates range from 2% to 10% of patients on long-term opioid therapy. It’s likely underdiagnosed because many doctors mistake it for tolerance or disease progression. In high-dose or intravenous users, the rate may be higher.

Can genetic testing help identify risk for OIH?

Potentially. Variants in the COMT gene affect how your body breaks down pain-related chemicals like dopamine. People with low-activity COMT variants are more sensitive to pain and may be at higher risk for OIH. While not yet routine, genetic testing is being studied as a tool to personalize opioid therapy.

Does kidney disease increase the risk of OIH?

Yes. Kidneys help clear opioid metabolites like morphine-3-glucuronide. If they’re not working well, these metabolites build up and act as nerve irritants, increasing pain sensitivity. Patients with kidney disease on opioids need closer monitoring for signs of OIH.

Jodi Olson

January 30, 2026 AT 13:19It’s not paradoxical-it’s predictable. The nervous system adapts to sustained chemical suppression by becoming hypersensitive. This isn’t medicine failing. It’s biology asserting its primacy over pharmacology.

Every time we treat symptoms without addressing systemic dysregulation, we deepen the wound.

Pharmaceutical intervention, when divorced from neuroplasticity and environmental context, becomes its own pathology.

We’ve turned pain into a commodity to be dosed, not a signal to be understood.

Maybe the real question isn’t how to stop OIH-but how we let it happen in the first place.

Amy Insalaco

January 31, 2026 AT 00:48One must distinguish between pharmacodynamic tolerance and opioid-induced hyperalgesia, which is a distinct neuroadaptive phenomenon mediated by NMDA receptor upregulation and dynorphinergic disinhibition within the dorsal horn-particularly in the context of mu-opioid receptor internalization cascades.

Moreover, the presence of morphine-3-glucuronide, a neuroexcitatory metabolite, further exacerbates central sensitization via glial activation and proinflammatory cytokine release, especially in renal insufficiency.

It’s astonishing how many clinicians conflate this with psychological amplification or noncompliance, when the neurobiology is so clearly delineated in the literature since the 1990s.

And yet, we still treat chronic pain as if it were a linear equation rather than a dynamic, maladaptive neural network.

Frankly, the persistence of this diagnostic ignorance is a scandal.

owori patrick

February 1, 2026 AT 02:15This is something I’ve seen in my community-people on long-term pain meds, slowly losing their quality of life without knowing why.

I’ve talked to folks who were told they were ‘just being dramatic’ when their skin started hurting from clothes.

But it’s real.

And we need more doctors who listen, not just prescribe.

If we can help someone understand this, maybe they won’t feel so alone in the struggle.

Thank you for writing this clearly.

It’s a gift to people who’ve been ignored.

Claire Wiltshire

February 2, 2026 AT 13:42Excellent breakdown of a critically underrecognized condition. I’d like to add that the diagnostic challenge is compounded by the fact that many patients are already on multiple CNS-active medications, making it difficult to isolate the contribution of opioids.

Additionally, while methadone is a strong option due to its NMDA antagonism, access is limited in many regions due to regulatory barriers and stigma surrounding its use for pain management.

Also worth noting: pregabalin and gabapentin should be titrated slowly-many patients experience dizziness or sedation if ramped up too quickly, which can lead to premature discontinuation.

And yes, CBT and graded exposure therapy are not ‘alternative’ treatments-they’re neurorehabilitative. The brain rewires with consistent, guided input.

Thank you for emphasizing that this isn’t a failure of will, but a biological response.

Donna Fleetwood

February 3, 2026 AT 21:48Just wanted to say this gave me hope.

I’ve been on oxycodone for 5 years and my pain got worse every time I increased the dose.

My doctor finally listened when I showed him this article.

We’re tapering now.

It’s scary, but for the first time in years, I feel like there’s a path forward.

Thank you.

Melissa Cogswell

February 4, 2026 AT 20:48Regarding the COMT gene variant-yes, the Val158Met polymorphism is well-documented in pain sensitivity literature. Those with Met/Met homozygosity have lower enzymatic activity, leading to elevated synaptic dopamine and norepinephrine, which potentiates descending facilitation pathways.

It’s a known risk factor for fibromyalgia and OIH.

Still, genetic testing isn’t widely available in primary care.

Maybe we need a simple clinical algorithm to screen for high-risk patients before long-term opioid initiation.

Bobbi Van Riet

February 6, 2026 AT 06:04I’ve had OIH. I didn’t know what it was until my pain specialist finally said the words.

For years I thought I was broken-like my body was just failing me.

Then I realized: it wasn’t failing. It was fighting.

Switching to methadone was the hardest thing I’ve ever done-physically and emotionally.

The first month was hell. Tremors, insomnia, crying for no reason.

But by month three, I could wear a t-shirt again without flinching.

I still take gabapentin. I still do yoga. I still have pain.

But now I know it’s not because I’m weak.

It’s because my nerves got loud.

And now, slowly, they’re learning to be quiet again.

Thank you for naming it. So many people don’t even know it’s a thing.

Beth Beltway

February 7, 2026 AT 15:28Stop romanticizing this. This isn’t some noble biological tragedy-it’s the predictable consequence of lazy medicine and patient entitlement.

You think this is about ‘nerves’? No. It’s about people who refused to try physical therapy, refused to lose weight, refused to accept that pain isn’t always fixable.

And now you want to blame opioids? No-you blame the system.

But the system didn’t force you to take 200mg of morphine equivalents daily for a herniated disc.

Doctors are just tired of being manipulated into enabling dependency under the guise of ‘pain relief.’

Stop pretending this is a medical mystery. It’s a behavioral one.

And until we stop rewarding poor choices with more pills, nothing will change.