Graves' disease is the most common cause of hyperthyroidism in the United States, accounting for about 80% of all cases. It’s not just an overactive thyroid-it’s an autoimmune disorder where your immune system mistakenly attacks your own thyroid gland. This triggers the production of abnormal antibodies called thyroid-stimulating immunoglobulins (TSI), which force the thyroid to pump out too much hormone. The result? A body running too fast: racing heart, unexplained weight loss, shaking hands, insomnia, and intense anxiety. Left untreated, Graves’ can lead to heart failure, bone loss, and even thyroid storm-a medical emergency with a 20-30% death rate.

What Makes Graves’ Disease Different?

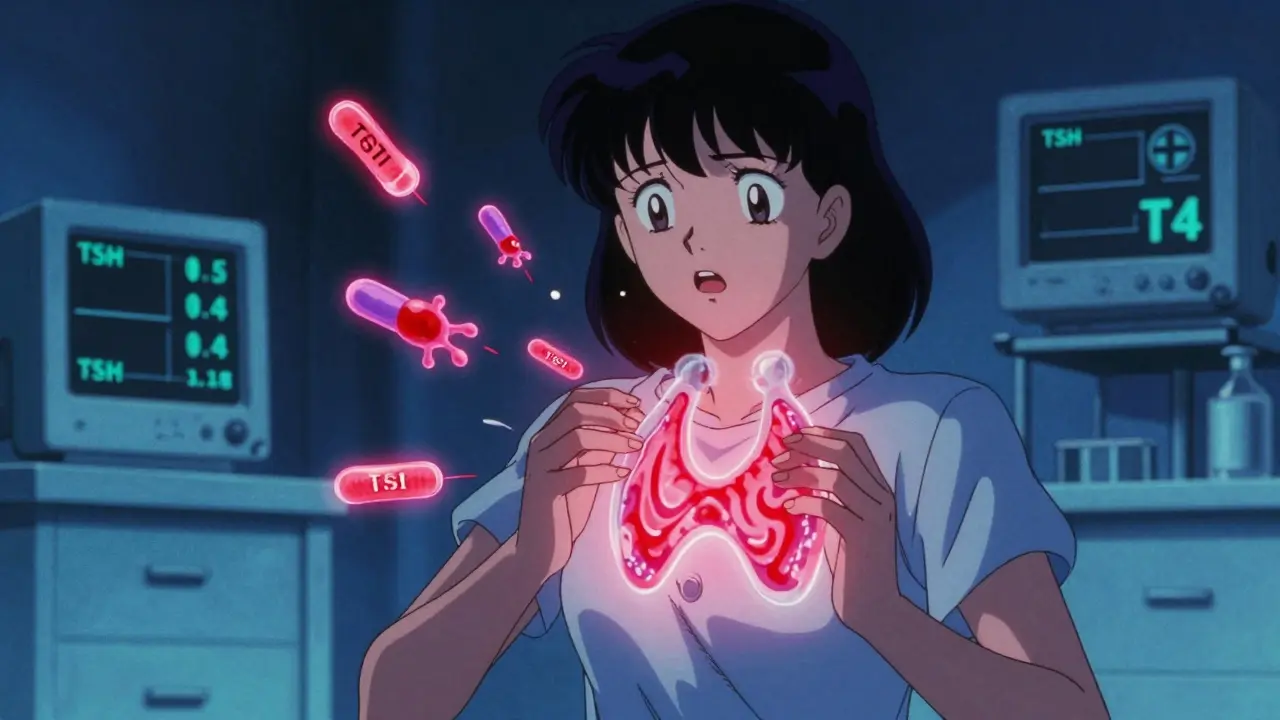

Not all hyperthyroidism is the same. In Graves’ disease, you don’t just have high thyroid hormone levels-you also get unique symptoms that point directly to the autoimmune root. About 30-50% of patients develop Graves’ ophthalmopathy: bulging eyes, redness, double vision, or even vision loss from optic nerve pressure. Around 1-4% get dermopathy, a rare, painless, lumpy rash on the shins or tops of feet. These aren’t random side effects-they’re diagnostic clues. If you have hyperthyroidism plus eye or skin changes, it’s almost certainly Graves’.Diagnosis relies on blood tests. A suppressed TSH (below 0.4 mIU/L) with high free T4 (above 1.8 ng/dL) and free T3 (above 4.2 pg/mL) is the classic pattern. But the real key is the TRAb test, which detects those rogue antibodies. It’s 90-95% accurate at confirming Graves’ and helps predict whether you’re likely to relapse after treatment. If your TRAb level is over 10 IU/L, you have an 80% chance of the disease coming back after stopping medication.

Why PTU? The Role of Propylthiouracil in Treatment

The first line of treatment for most adults is methimazole-a once-daily pill that blocks thyroid hormone production. But there’s one group where PTU (propylthiouracil) is still the go-to: pregnant women in their first trimester. Why? Because methimazole carries a small but real risk of birth defects, especially in the first 12 weeks. PTU, while not perfect, has a lower chance of harming the developing baby.PTU works faster than methimazole, which is why it’s also used in thyroid storm-the life-threatening surge of thyroid hormones that can cause fever over 102°F, rapid heartbeat, confusion, and vomiting. In those emergencies, PTU is often given intravenously to shut down hormone production quickly.

But PTU has a dark side: liver damage. About 0.2-0.5% of patients develop severe hepatotoxicity, sometimes leading to liver failure. That’s why anyone on PTU needs monthly liver function tests. If you notice yellow skin, dark urine, nausea, or right-side abdominal pain, stop the drug immediately and get help. The FDA requires a black box warning on PTU for this reason.

Patients on PTU also report more side effects: a metallic taste, joint pain, and skin rashes. One patient on a Graves’ forum wrote, “PTU saved my pregnancy, but the monthly blood draws for liver tests felt like a punishment.” That’s the trade-off-life-saving for the baby, but a heavy burden for the mother.

How PTU Compares to Other Treatments

There are three main ways to treat Graves’ disease: drugs, radioactive iodine, and surgery.- Antithyroid drugs (ATDs) like PTU and methimazole control the disease but don’t cure it. About 30-50% of people go into remission after 12-18 months of treatment. The rest relapse, often within a year of stopping.

- Radioactive iodine (I-131) destroys the thyroid over weeks to months. It’s effective in 80-90% of cases, but nearly everyone ends up hypothyroid and needs lifelong thyroid hormone replacement. It’s not used in pregnancy or breastfeeding.

- Thyroidectomy removes the gland surgically. It works fast, with a 95% success rate, but carries risks: damage to the voice box (1%) or parathyroid glands (1-2%), which control calcium levels.

Costs vary widely. ATDs cost $10-$50 a month. Radioactive iodine runs $300-$1,500. Surgery? $5,000-$15,000. Insurance usually covers all three, but out-of-pocket costs can add up, especially if complications arise.

Who Needs PTU Today?

PTU isn’t the first choice for most people anymore. Methimazole is safer for long-term use, with fewer liver risks and easier dosing. But PTU still has a critical place:- First-trimester pregnancy

- Thyroid storm

- Patients allergic or intolerant to methimazole

- Those who relapse after methimazole and can’t or won’t do radiation or surgery

Endocrinologists now use TRAb levels to guide decisions. If your antibodies are still high after 12 months of treatment, they’ll likely recommend moving to radioactive iodine or surgery instead of continuing drugs. PTU is a bridge, not a destination.

What Happens After Treatment?

Even if your thyroid levels normalize, Graves’ doesn’t always go away. About 40-60% of people relapse within a year of stopping medication. That’s why doctors don’t rush to quit treatment. Monitoring TSH every 4-6 weeks during the first few months, then every 2-3 months, is standard. You also need to watch for signs your thyroid is underactive-fatigue, weight gain, cold intolerance-because too much medication can cause it.Eye symptoms are another long-term issue. Even after thyroid levels are normal, 40% of patients still have eye problems. Some need steroids, radiation, or even eye surgery. A new drug called teprotumumab, approved in 2021, reduces bulging eyes by 71% in clinical trials-but it costs $150,000 per course. Most patients still rely on corticosteroids or orbital radiation.

Living With Graves’ Disease

Patients often describe the pre-diagnosis period as a nightmare. On average, it takes 6-12 months to get diagnosed because symptoms mimic anxiety, depression, or menopause. One Reddit user wrote: “I was told I was just stressed. I lost 18 pounds in three months and couldn’t sleep. No one checked my thyroid until I collapsed.”Once diagnosed, managing Graves’ becomes a daily routine. Taking pills on time. Monitoring your heart rate. Watching for fever or sore throat (signs of rare but dangerous agranulocytosis). Keeping up with blood tests. Many patients feel isolated-especially those on PTU, who face extra monitoring and stigma around liver risk.

Support groups help. The Graves’ Disease and Thyroid Foundation runs a 24/7 helpline. Online communities like r/GravesDisease have over 12,500 members sharing tips, fears, and wins. The good news? 75% of patients reach normal thyroid levels within three months of starting the right treatment. Quality of life improves dramatically once hormones stabilize.

The Future of Graves’ Treatment

Research is moving fast. In 2022, the FDA approved the first home thyroid monitor, ThyroidTrack, which lets patients check TSH levels with a finger-prick device. It’s still limited to research use, but it could change how we manage chronic thyroid disease.New drugs like rituximab (a B-cell depleter) and TSH receptor blockers (like K1-70) are in trials. Early results show promise: K1-70 normalized thyroid function in 85% of patients without causing hypothyroidism. That could be a game-changer-treating the cause, not just the symptoms.

Genetic research is also advancing. People with the HLA-DR3 gene have a threefold higher risk of Graves’ disease. In the next five years, we may see personalized treatment plans based on your DNA, immune profile, and antibody levels-no more trial and error.

For now, PTU remains a vital tool-flawed, risky, but irreplaceable for certain patients. It’s not about choosing the “best” drug. It’s about choosing the right one for your life: your age, your plans, your body, and your risks.

Is PTU safe during pregnancy?

PTU is considered safer than methimazole during the first trimester of pregnancy because it crosses the placenta less and has a lower risk of causing birth defects. However, it carries a small but serious risk of liver damage, so it’s only used when necessary and with close monitoring. After the first trimester, most doctors switch patients back to methimazole due to PTU’s higher liver toxicity risk.

Can Graves’ disease be cured?

Graves’ disease can go into remission-about 30-50% of patients do after 12-18 months of antithyroid medication. But it’s not a true cure. Relapse rates are high, at 40-60%, especially if thyroid antibodies remain elevated. Radioactive iodine and surgery can eliminate the overactive thyroid, but they lead to permanent hypothyroidism, which requires lifelong hormone replacement.

What are the signs of PTU liver damage?

Symptoms include yellowing of the skin or eyes (jaundice), dark urine, nausea, vomiting, loss of appetite, abdominal pain on the right side, and extreme fatigue. If you experience any of these while taking PTU, stop the medication immediately and seek emergency care. Liver damage can develop quickly and become life-threatening.

Why do some people with Graves’ still have eye problems after treatment?

Graves’ eye disease is driven by the immune system, not just thyroid hormone levels. Even when thyroid function is normal, the immune attack on the eye tissues can continue. This is why eye symptoms often persist or even worsen after thyroid treatment. Specialized care from an ophthalmologist-using steroids, radiation, or newer drugs like teprotumumab-is often needed.

How long do you take PTU for Graves’ disease?

PTU is usually started at a higher dose (100-150 mg three times daily) and gradually reduced as thyroid levels normalize. Most patients take it for 12-18 months, but in pregnancy, it may be continued longer. The goal is to reach the lowest effective dose while monitoring for side effects. If remission occurs, the drug is slowly stopped under medical supervision.

What to Do Next

If you’ve been diagnosed with Graves’ disease, don’t panic. Treatment works. But you need to be an active partner in your care. Ask for TRAb testing at diagnosis and follow-up. Discuss whether PTU or methimazole is right for you-especially if you’re pregnant, planning pregnancy, or have liver concerns. Monitor your symptoms closely. Report any new pain, fever, or skin changes. And don’t wait months to get answers-if your doctor dismisses your symptoms, seek a second opinion from an endocrinologist.Graves’ disease isn’t just a thyroid problem. It’s a whole-body condition that affects your heart, eyes, bones, and mental health. The right treatment-whether it’s PTU, radioactive iodine, or surgery-can restore your life. But only if you understand the risks, the options, and your own body’s signals.

Dev Sawner

December 19, 2025 AT 10:16While the article presents a clinically accurate overview, it conspicuously omits the fact that PTU’s hepatotoxicity profile is well-documented in peer-reviewed hepatology journals since 1987. The FDA black box warning was issued after 17 documented fatalities in the U.S. alone between 2002 and 2010. To suggest PTU is merely a 'bridge' is medically irresponsible without emphasizing mandatory monthly LFTs and patient education protocols. The omission of ALP and bilirubin thresholds in monitoring guidelines is a critical flaw in this otherwise meticulous exposition.

Moses Odumbe

December 19, 2025 AT 11:47PTU saved my life during my first trimester 😭 but the liver tests? Absolute nightmare. Monthly needles, sweating over results, feeling like a lab rat. Still better than risking my baby’s face being melted by methimazole. 🤕💉 #GravesWarrior

Kelly Mulder

December 20, 2025 AT 04:30It is profoundly disturbing that this article casually refers to PTU as 'vital' without adequately contextualizing its mortality risk. The author's tone borders on negligence. One does not casually prescribe a drug with a 0.5% chance of acute hepatic necrosis without first ensuring the patient has undergone a full psychiatric evaluation for compliance capability. This is not medicine. This is roulette with a liver.

Elaine Douglass

December 20, 2025 AT 14:59i just want to say thank you for writing this. i was diagnosed last year and everyone kept telling me i was just anxious. i lost 20 lbs in 4 months and no one checked my thyroid. when i finally got tested and found out it was graves, i cried for an hour. PTU was rough but it worked. the eye thing still sucks though. you’re not alone ❤️

Takeysha Turnquest

December 21, 2025 AT 22:09Graves’ isn’t a disease. It’s a rebellion of the self. The body, betrayed by its own immune system, screams in hormones. PTU? A temporary ceasefire in a war we didn’t start. The thyroid doesn’t want to burn. It never did. We just forgot how to listen.

And yet… we still measure life in TSH levels. As if the soul can be quantified by a lab report.

Alex Curran

December 23, 2025 AT 14:49For anyone considering PTU in pregnancy, make sure your endo has a plan for switching to methimazole after 12 weeks. I was on PTU until week 14 and had a near miss with elevated ALT. The switch was smooth but the anxiety wasn't. Also, get baseline eye exams even if you feel fine. Ophthalmopathy can sneak up. And yes, teprotumumab is crazy expensive but some nonprofits help with copays. Ask your social worker.

Lynsey Tyson

December 24, 2025 AT 22:56thank you for sharing this. i’ve been on methimazole for 3 years and relapsed twice. i’m scared to try PTU because of the liver thing but i’m also scared of radioactive iodine because i want kids someday. it’s such a tightrope. i just wish doctors talked more about the emotional toll, not just the numbers

Edington Renwick

December 25, 2025 AT 08:53Let’s be honest - PTU is a relic. A band-aid on a bullet wound. The fact that we still use a drug with a black box warning in 2024 is a failure of pharmaceutical innovation. We’ve got CRISPR, mRNA vaccines, AI diagnostics - and we’re still poisoning people’s livers to stabilize their thyroids? This isn’t medicine. It’s survivalism with a prescription pad.

Sarah McQuillan

December 25, 2025 AT 17:58Why is PTU still allowed in the US? The FDA is clearly in the pocket of Big Pharma. Did you know that the same company that makes PTU also owns patents on thyroid replacement drugs? This isn’t about safety - it’s about profit. They need you dependent. They need you coming back every month. They need your insurance to pay for those liver tests. Wake up.

Aboobakar Muhammedali

December 25, 2025 AT 18:44as someone from india i can say we use ptu more than methimazole here because it's cheaper and more available. no one talks about this but in rural areas we don't have access to regular blood tests. so we just give methimazole and hope. my cousin died from liver failure on ptu but her family couldn't afford the monthly labs. this isn't just medical. it's class.

Laura Hamill

December 26, 2025 AT 19:34THEY DON’T WANT YOU TO KNOW THIS BUT PTU IS PART OF A BIGGER COVERUP. THE THYROID ISN’T EVEN THE PROBLEM. THE REAL ISSUE IS FLUORIDE IN THE WATER SUPPLY. IT MIMICS TSH RECEPTORS. THAT’S WHY GRAVES’ IS SPREADING. THE CDC KNOWS. THE FDA KNOWS. THEY’RE JUST WAITING FOR YOU TO GET DEPENDENT ON DRUGS SO THEY CAN SELL YOU THE CURE. TEPROTUMUMAB? THAT’S JUST A SMOKE SCREEN. CHECK THE FLUORIDE LEVELS IN YOUR TOWN. THEY’RE HIDING IT.