Shift-Work Heart Risk Calculator

This calculator estimates your risk of developing cardiovascular disease due to shift-work patterns. Enter your details below to get personalized risk assessment.

Your Risk Assessment:

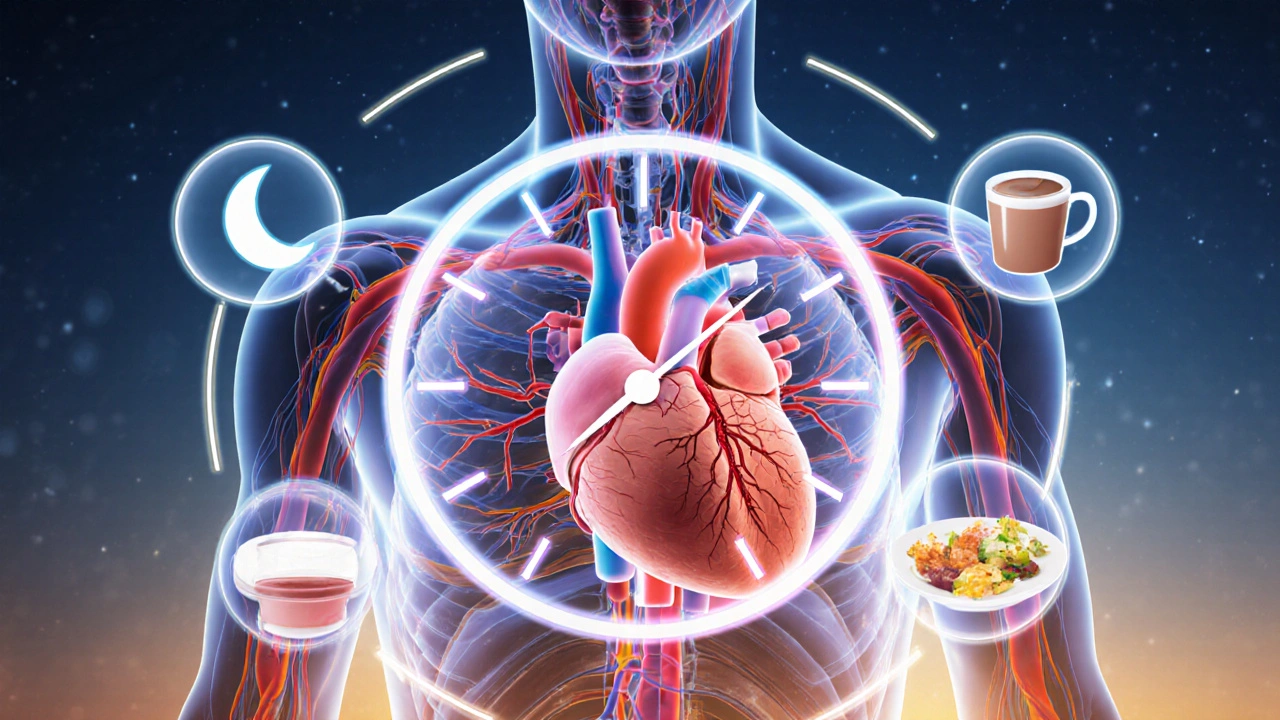

When you hear about night‑shift nurses, factory workers, or emergency‑room doctors, the focus is usually on fatigue and burnout. Few realize that the same irregular schedule can quietly raise the odds of a heart attack, stroke, or chronic artery blockage. Understanding the link between shift-work disorder and cardiovascular disease helps employees, managers, and clinicians spot warning signs early and act before a serious event occurs.

Key Takeaways

- Shift-Work Disorder is a chronic misalignment of the internal clock that raises blood‑pressure, cholesterol, and inflammation levels.

- People with SWD face a 20‑40% higher risk of cardiovascular disease compared with day‑time workers.

- Disrupted circadian rhythm, sleep loss, and unhealthy eating patterns drive most of the risk.

- Regular screening of blood pressure, cholesterol, and markers of inflammation can catch problems early.

- Simple changes-consistent light exposure, timed meals, and strategic naps-significantly lower heart‑disease risk for night‑shift workers.

What Is Shift-Work Disorder?

Shift-Work Disorder is a sleep‑wake condition that occurs when a person's work schedule clashes with the natural light‑dark cycle. The body’s master clock, located in the suprachiasmatic nucleus, expects darkness at night and light during the day. When someone regularly works nights or rotating schedules, this clock is forced to run on an abnormal timetable, leading to chronic fatigue, insomnia, and daytime sleepiness.

Diagnostic criteria (DSM‑5) require at least three months of persistent sleep problems directly linked to work timing, accompanied by functional impairment. About 10‑15% of shift workers meet these criteria, but many more experience sub‑clinical symptoms that still affect health.

Cardiovascular Disease: The Big Picture

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is an umbrella term for conditions that involve the heart or blood vessels-such as coronary artery disease, heart failure, and stroke. Globally, CVD accounts for over 17million deaths each year, making it the leading cause of mortality. Traditional risk factors include high blood pressure, elevated cholesterol, smoking, diabetes, and a sedentary lifestyle.

Emerging evidence shows that work‑related sleep disruption adds a new, modifiable risk factor to this list. The connection isn’t just statistical; it’s rooted in biology.

Evidence Linking Shift-Work Disorder to Heart Disease

Large‑scale epidemiological studies have repeatedly shown a heightened CVD risk among shift workers. A 2023 meta‑analysis of 18 cohort studies (over 2million participants) reported a pooled relative risk (RR) of 1.27 for coronary heart disease and 1.34 for stroke among those with confirmed SWD.

Key findings from three landmark studies illustrate the trend:

- Harvard Nurses’ Health Study (2020): Night‑shift nurses had a 31% higher incidence of myocardial infarction after a 10‑year follow‑up, even after adjusting for smoking, BMI, and family history.

- European Working Conditions Survey (2022): Rotating‑shift factory workers in Germany showed a 22% increase in hypertension prevalence compared with day‑only peers.

- Australian Defence Force Cohort (2024): Personnel on 24‑hour duty cycles exhibited a 38% rise in arterial plaque thickness measured by carotid ultrasound.

These studies share a common thread: the longer the exposure to irregular schedules, the greater the cardiovascular toll.

Biological Mechanisms Behind the Connection

Several pathways translate a broken circadian rhythm into heart disease:

- Circadian rhythm disruption alters the daily release of hormones like cortisol and melatonin. Elevated nighttime cortisol spikes blood‑pressure and platelet aggregation, while reduced melatonin removes its protective antioxidant effect.

- Chronic sleep deprivation raises sympathetic nervous‑system activity, leading to higher resting heart rate and vasoconstriction.

- Irregular eating times cause metabolic dysregulation-higher fasting glucose, increased cholesterol LDL, and lower HDL-hallmarks of metabolic syndrome.

- Inflammatory markers (CRP, IL‑6) rise by 15‑30% in shift workers, fostering endothelial damage that accelerates atherosclerosis.

- Disrupted timing of blood‑pressure dipping (normally lower at night) results in “non‑dipping” hypertension, a known predictor of stroke.

When these factors combine, they create a perfect storm for plaque buildup, clot formation, and eventual cardiac events.

Who’s Most at Risk?

Not every night‑shift employee will develop CVD, but certain groups face higher odds:

- Age over 45: Age‑related vascular stiffening amplifies the impact of sleep loss.

- Male sex: Men historically have higher baseline CVD rates, and the shift‑work effect appears slightly stronger.

- Pre‑existing metabolic conditions (type 2 diabetes, obesity): These conditions already elevate cholesterol and inflammation, so added circadian stress pushes risk further.

- Long‑term exposure: More than five years of rotating or permanent night shifts correlates with a steeper risk curve.

- Lack of recovery sleep: Workers who cannot secure ≥7hours of consolidated sleep on off‑days show the greatest blood‑pressure spikes.

Prevention and Management Strategies

Employers and individuals can tackle the problem from both sides-workplace design and personal habits.

Workplace Interventions

- Stable schedules: Fixed night shifts are less harmful than rotating patterns because the body can eventually adjust.

- Forward‑rotating shifts: Moving from morning → afternoon → night (instead of backward) aligns better with natural circadian progression.

- Bright‑light exposure: Installing high‑intensity LED lights during the night shift helps suppress melatonin at the right time, improving alertness and reducing cortisol spikes.

- Scheduled breaks: Short 15‑minute “power‑nap” windows between 2-4am have been shown to lower systolic pressure by up to 5mmHg.

- Health monitoring: Annual cardiovascular screenings (BP, lipid panel, CRP) for all shift workers allow early detection.

Individual Lifestyle Tweaks

- Consistent sleep window: Even on days off, aim for the same bedtime and wake‑time ±1hour.

- Light hygiene: Wear sunglasses on the way home after a night shift to limit morning light exposure; use blackout curtains to protect daytime sleep.

- Timed meals: Keep the main calorie intake during the biological day (e.g., eat a substantial meal before the night shift starts, light snack during, and a protein‑rich breakfast after the shift ends).

- Physical activity: 30minutes of moderate exercise within 2hours of waking supports glucose regulation and blood‑pressure dipping.

- Stress reduction: Mindfulness or brief breathing exercises before bedtime improve sleep onset latency.

Clinical Guidelines & Screening Recommendations

Several professional bodies now mention shift work as a risk modifier. The American Heart Association (2023) suggests adding chronic shift schedule to the traditional CVD risk calculator. For patients with confirmed SWD, clinicians should:

- Measure resting blood pressure on both work and off days.

- Order a fasting lipid panel at least annually.

- Check high‑sensitivity C‑reactive protein (hs‑CRP) to assess low‑grade inflammation.

- Discuss sleep‑hygiene interventions and, when needed, refer to a sleep‑medicine specialist.

- Consider low‑dose aspirin only if the 10‑year ASCVD risk exceeds 10% and bleeding risk is low.

Early identification can shift a patient from a high‑risk trajectory to a manageable one.

Comparison of Cardiovascular Risk: Shift Workers vs. Day Workers

| Marker | Day‑time Workers (Reference) | Shift Workers | Risk Increase |

|---|---|---|---|

| Systolic Blood Pressure | 120mmHg | 128mmHg | +6.7% |

| LDL‑Cholesterol | 110mg/dL | 126mg/dL | +14.5% |

| hs‑CRP (Inflammation) | 1.2mg/L | 2.0mg/L | +66% |

| Incidence of Myocardial Infarction | 3.2per1,000yr | 4.3per1,000yr | +34% |

| Stroke | 2.1per1,000yr | 2.9per1,000yr | +38% |

Next Steps for Employers and Employees

If you manage a workforce that includes night or rotating shifts, start by auditing current schedules. Identify roles with the longest continuous night exposure and pilot a forward‑rotating roster. Pair schedule changes with onsite health checks and education sessions on sleep hygiene.

For individual workers, ask your supervisor for a written shift pattern, track your sleep and blood‑pressure at home, and bring the data to your primary care visit. A simple spreadsheet can reveal patterns that doctors may otherwise miss.

Frequently Asked Questions

Does occasional night shift increase heart risk?

One‑off night shifts have a minimal impact. The risk rises significantly after repeated exposure (usually >3 nights per week for several months). Consistency is the key driver, not a single occasional shift.

Can melatonin supplements counteract the damage?

Melatonin can help reset the sleep‑wake cycle, but evidence for long‑term cardiovascular protection is limited. Use it under medical guidance and combine it with light‑therapy and proper sleep timing for best results.

Are there specific foods that lower the risk for shift workers?

A diet rich in omega‑3 fatty acids, fiber, and low‑glycemic carbs helps control cholesterol and glucose spikes that are common after night shifts. Avoid heavy, processed meals close to the end of a night shift, as they can impair sleep and raise triglycerides.

Should I get an ECG if I work nights?

Routine ECGs are not required for every shift worker. However, if you have hypertension, high cholesterol, or a family history of heart disease, an annual ECG can catch silent arrhythmias early.

What’s the best way to nap during a night shift?

A 20‑minute power nap between 2-4am, in a dark, quiet space, restores alertness without causing sleep inertia. Longer naps (90minutes) are useful if you can afford the time, as they complete a full sleep cycle.

Annie Tian

October 3, 2025 AT 17:38What a thorough walk‑through of the cardiovascular risks tied to shift work, and kudos for the practical calculator! This tool gives night‑shift nurses, factory crews, and ER docs a concrete way to gauge their heart health, and the layered advice-from light‑therapy to timed meals-covers every angle, making the science accessible, actionable, and, most importantly, hopeful for anyone battling the clock.

April Knof

October 14, 2025 AT 03:31It's fascinating how cultural expectations around work hours shape our biology. In societies where late‑night markets are the norm, people often develop informal strategies-like post‑dinner walks or early morning tea-that unintentionally buffer some of the circadian stress, showing that community practices can be a hidden ally against the heart risks outlined here.

Tina Johnson

October 24, 2025 AT 13:23While the article is comprehensive, it neglects to address the socioeconomic gradient that determines who ends up on night shifts in the first place; low‑wage workers are disproportionately assigned to rotating schedules, yet the piece offers generic lifestyle tips without acknowledging the structural barriers that limit their ability to implement such recommendations.

Sharon Cohen

November 3, 2025 AT 22:16I doubt the whole shift‑work hype is justified.

Rebecca Mikell

November 14, 2025 AT 08:09Great synthesis of the data, and I especially appreciate the clear table comparing blood‑pressure and cholesterol differences. The emphasis on regular screenings and simple sleep‑hygiene tweaks feels both realistic and empowering for workers who feel trapped in their schedules.

Ellie Hartman

November 24, 2025 AT 18:02Thank you for pointing out the socioeconomic angle, Tina. Even if systemic change is slow, we can still advocate for employer‑provided health checks and flexible scheduling, which are tangible steps that can mitigate some of the disparities you mentioned.

Alyssa Griffiths

December 5, 2025 AT 03:55Don't forget that many of those health‑check programs are funded by big pharma, which subtly pushes medication over lifestyle changes; the real solution might involve questioning why the industry has such a vested interest in keeping workers on the night shift in the first place.

Jason Divinity

December 15, 2025 AT 13:48Permit me to articulate, with the utmost linguistic precision, that the exposition herein succeeds admirably in delineating the pathophysiological cascade linking nocturnal labor to atherosclerotic progression; however, the author neglects to interrogate the geopolitical forces that perpetuate such deleterious occupational structures, thereby rendering the treatise both enlightening and incomplete.

Edd Dan

December 25, 2025 AT 23:41Sorry to interrupt, but I think "geopolitical" might be a tad strong here – maybe "policy" fits better? Also, just a tiny typo: "delineating" was spelled with an extra "e" earlier.

Fatima Sami

January 5, 2026 AT 09:34The article’s data tables are well‑formatted, yet the narrative sometimes slips into colloquialisms that undermine its scholarly tone; a more disciplined prose would enhance credibility among medical professionals.

Arjun Santhosh

January 15, 2026 AT 19:27Totally get where you're coming from, Fatima – the info is solid, just needs that little polish. Keep it up!

Stephanie Jones

January 26, 2026 AT 05:20Beyond the statistics lies the unsettling truth that our modern economy thrives on bending human biology to its will, rendering us vulnerable to the very diseases we claim to combat; perhaps the greatest risk is not the heart condition itself, but the surrender of our natural rhythms to profit‑driven schedules.

Nathan Hamer

February 5, 2026 AT 15:13Reading through this piece feels like embarking on a journey through the hidden corridors of our bodies, where each shift‑work night is a flickering candle in a long hallway; the author paints a vivid tableau of hormonal upheaval, with cortisol surging like an uninvited guest at a midnight banquet, while melatonin quietly retreats to the shadows, leaving our hearts beating a frantic drum. The data on elevated LDL and hs‑CRP levels read like warning signs on a road trip, urging drivers to pull over and check their tires. Yet the advice offered-consistent light exposure, strategic naps, and timed meals-acts as a gentle guide, a compass pointing toward safer terrain. I especially love the suggestion to harness bright‑light therapy, turning the office into a sunrise for those who labor under the stars. Moreover, the emphasis on regular cardiovascular screenings is akin to checking the engine oil before a long haul, preventing catastrophic breakdowns. The table comparing systolic pressure and cholesterol between day‑time and shift workers serves as a clear map, illustrating the hidden elevations that might otherwise go unnoticed. While the article mentions the 20‑40% increased risk, it could further explore how individual genetics modulate that percentage, adding depth to the risk calculator. The inclusion of lifestyle hacks-like a protein‑rich breakfast post‑shift-mirrors the practice of refueling a vehicle with premium fuel after a tough drive. As we digest this information, it's crucial to remember that every small adjustment compounds, much like regular oil changes extend a car’s lifespan. The call to action for employers to audit schedules resonates strongly; after all, a well‑maintained fleet is only as good as the routes it follows. Ultimately, this guide transforms abstract numbers into actionable steps, empowering night‑owls to protect their ticking hearts, one deliberate habit at a time.

Tom Smith

February 16, 2026 AT 01:06Oh, brilliant, because what we really needed was a 15‑sentence love letter to cholesterol. Thanks for the novella; I'll be sure to skim it during my coffee break.

Kyah Chan

February 26, 2026 AT 10:59From a methodological standpoint, the synthesis of epidemiological data with mechanistic pathways is commendable; however, the reliance on self‑reported shift patterns introduces potential bias, which could be mitigated by integrating objective actigraphy data in future analyses.