Why Post-Marketing Drug Safety Tracking Matters

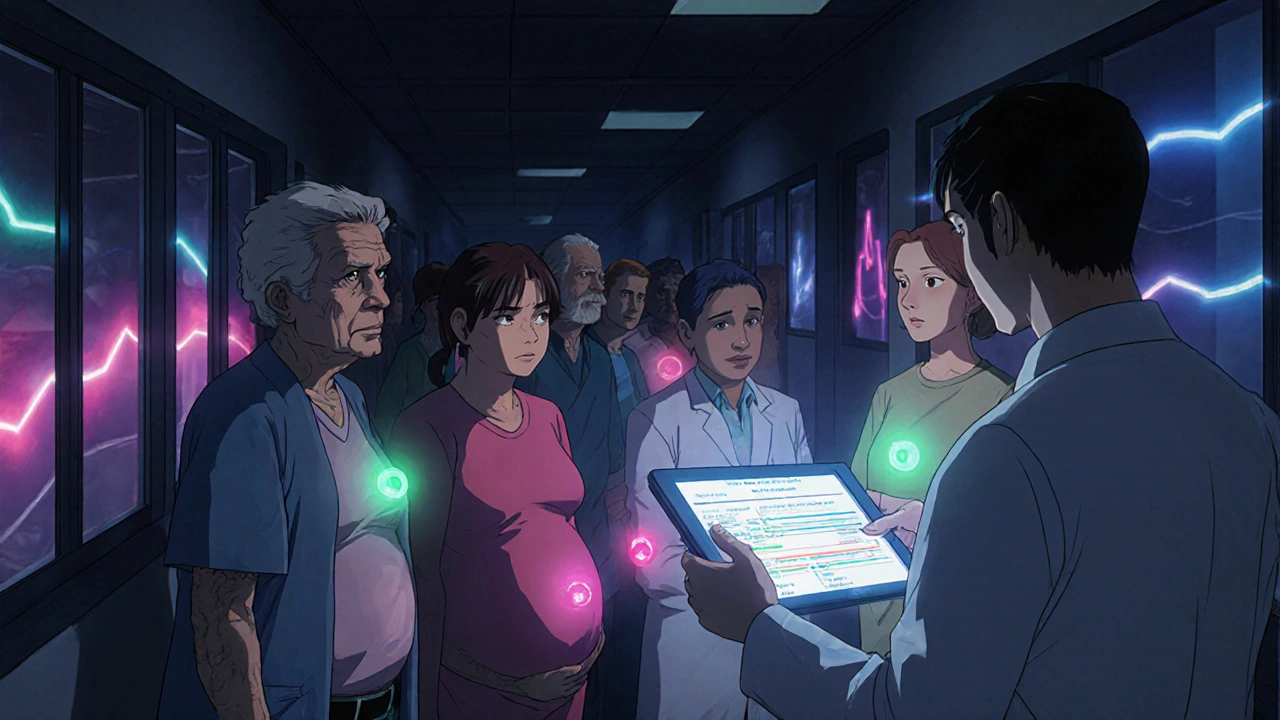

Drugs approved by regulators like the FDA or EMA aren’t tested on millions of people before they hit the market. Clinical trials usually involve a few thousand patients under strict conditions. That means rare side effects, interactions with other medications, or risks in older adults or pregnant women often go unnoticed until the drug is widely used. That’s where post-marketing surveillance comes in. It’s not a backup plan-it’s the real-world safety net that catches problems clinical trials missed.

Take the case of a common painkiller. In trials, it might seem safe for most adults. But once millions of elderly patients start taking it daily, kidney damage shows up in 1 in 500 users. Without post-marketing tracking, that risk stays hidden. That’s why regulators require drugmakers to keep studying their products after approval. Tracking these studies isn’t optional-it’s how you protect patients long after the drug is sold.

The Core Systems Behind Drug Safety Monitoring

There are two main systems doing the heavy lifting in the U.S.: FAERS and Sentinel. They work differently but together cover more ground than either could alone.

FAERS (FDA Adverse Event Reporting System) is a database where doctors, pharmacists, patients, and drug companies report suspected side effects. As of 2023, it held over 30 million reports. Anyone can submit one-no proof needed. That means it’s full of noise, but also catches things no one expected. A nurse notices a pattern of heart rhythm issues in patients taking a new diabetes drug. She files a report. Months later, analysts spot the trend. That’s FAERS in action.

Sentinel is different. It doesn’t rely on reports. Instead, it pulls real data from electronic health records and insurance claims across 300 million Americans. It looks for patterns automatically: Are people on Drug X getting more liver failures than those on Drug Y? It’s faster and more precise than FAERS, but it can’t see what’s not recorded-like symptoms patients didn’t mention to their doctor.

In the UK, the Yellow Card system collects about 76,000 reports a year. Canada’s Vigilance Program gets nearly 29,000. These aren’t just numbers-they’re early warnings. The system that catches the first sign of a problem can prevent dozens of hospitalizations.

How Drug Companies Track Their Own Studies

When a drug gets approved, regulators often require the manufacturer to run specific post-marketing studies. These aren’t optional. They’re legally binding. The company must design them, recruit patients, collect data, and report results-usually within three years.

But here’s the problem: 72% of these studies run late. Why? Recruiting patients is hard. Getting data from hospitals is slow. Some companies use distributed data networks now, which let them access records across multiple health systems without moving data. That cut study start times from 14 months to under 9 months between 2018 and 2023.

Successful tracking means having a team dedicated to it. Experts recommend at least one pharmacovigilance specialist for every $500 million in annual sales. That person doesn’t just file reports-they monitor timelines, flag delays, and coordinate with hospitals, labs, and regulatory bodies. Without that focus, studies get buried under other priorities.

What Happens When a Safety Signal Is Found

Finding a problem is only the first step. What happens next determines whether patients are protected.

Most often-87% of the time-the response is a label update. The drug’s prescribing information gets rewritten to warn about the risk. Maybe it says, “Avoid in patients over 75” or “Monitor liver enzymes monthly.” That’s the most common fix.

Less common but more serious: a “Dear Health Care Professional” letter. That’s a direct message sent to doctors telling them to stop prescribing the drug in certain cases. In 2020-2022, the FDA sent out 147 such communications affecting 112 drugs.

Then there’s REMS-Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy. This adds extra controls. Maybe patients need to enroll in a registry. Maybe only certified pharmacies can dispense the drug. Only 3% of safety actions lead to REMS changes, but they’re used for high-risk drugs like those that cause birth defects.

Market withdrawal? Extremely rare. Less than 1% of cases. It usually only happens when the risk clearly outweighs the benefit and there’s no safe way to use the drug.

Tools and Technologies Making Tracking Better

Old-school methods are still used, but new tech is changing the game.

Machine learning and AI are now filtering through millions of reports to spot real signals faster. In 2018, false alarms made up 34% of flagged safety issues. By 2023, that dropped to 19% thanks to smarter algorithms. The FDA’s Sentinel Innovation Center uses Bayesian analysis to weigh how likely a side effect is truly linked to the drug-not just a coincidence.

Large Language Models (LLMs) are being tested to read unstructured notes in electronic health records. In a 2023 pilot, LLMs improved signal detection by 42%. But they also created 23% more false alarms. That’s a trade-off. Better detection, but more work to verify.

Future systems like Sentinel Common Data Model Plus (SCDM+) will add genetic data to the mix. By 2026, it’ll include genomic info for 50 million patients. That means we’ll soon know not just if a drug causes liver damage-but who’s genetically at higher risk.

What Goes Wrong-and How to Fix It

Tracking systems aren’t perfect. The biggest problem? Delayed studies. The FDA mandates studies be done in three years. On average, they take five and a half. Why? Lack of funding, poor coordination, and fragmented data systems.

Another issue: underrepresentation. Clinical trials rarely include enough older adults, children, or people with multiple chronic conditions. But those are the people who end up using the drugs. The EMA found that 28% of serious side effects in elderly patients were invisible in trials because those patients weren’t studied.

Fixing this means better design. Studies should start with clear goals: Who are we studying? What data do we need? How will we get it? And who’s responsible for each step? Companies that use centralized monitoring systems with automated alerts for missed deadlines see much higher on-time completion rates.

What You Can Do to Support Safe Drug Use

If you’re a patient, your reports matter. If you notice a new symptom after starting a drug-especially if it’s unusual or severe-tell your doctor. Ask them to file a report. You can also submit one yourself through your country’s reporting system.

If you’re a healthcare provider, don’t assume a side effect is “just a coincidence.” If you see the same issue in three patients on the same drug, document it clearly and report it. Your input could prevent harm to others.

For industry professionals, the key is structure. Use standardized metrics like the Post-Marketing Study Timeliness Index (PMSTI) to track progress. Assign ownership. Set internal deadlines earlier than the regulator’s. And never underestimate the power of good data collection-clean, consistent records make all the difference.

What’s Next for Drug Safety Tracking

By 2025, the EU will launch its AI-powered EudraVigilance system, designed to spot signals faster across 30 countries. The WHO is building a global network to share data between 100 countries by 2027. That means a safety signal in Japan could be spotted in Brazil within days.

The 21st Century Cures Act has already increased required post-marketing studies by 37% since 2017-especially for cancer, neurological, and immune drugs. More drugs, more scrutiny.

What’s clear is this: drug safety isn’t a one-time check. It’s an ongoing process. The moment a drug is approved, the real monitoring begins. And it only works if everyone-regulators, companies, doctors, and patients-plays their part.

Cynthia Springer

November 25, 2025 AT 17:28Also, the part about elderly patients being underrepresented in trials? That's terrifying. My grandma's on three of these meds and I had no idea she was basically a guinea pig.

Rachel Whip

November 27, 2025 AT 11:59Ezequiel adrian

November 28, 2025 AT 09:55Ali Miller

November 28, 2025 AT 19:57Meanwhile, China and Russia are using AI to monitor every pill taken by every citizen. We're still relying on doctors to remember to file a form? This is why America can't lead anymore. We're outsourcing our safety to corporate HR departments.

JAY OKE

November 29, 2025 AT 03:24Joe bailey

November 30, 2025 AT 19:16Amanda Wong

December 2, 2025 AT 04:54Stephen Adeyanju

December 3, 2025 AT 00:45they're literally still using fax machines for some of this and it makes me sick

james thomas

December 3, 2025 AT 19:31Deborah Williams

December 4, 2025 AT 09:48Maybe the real safety net isn’t FAERS or Sentinel. Maybe it’s humility.