Every year, more than 100 million refugees and displaced people live in overcrowded camps with little clean water, poor sanitation, and no access to regular healthcare. In these conditions, parasitic worms don’t just spread-they thrive. Hookworm, roundworm, whipworm, and pinworm infections are routine, not rare. Children lose weight. Mothers grow weak. Schools empty. And one cheap, simple drug-mebendazole-is often the only thing standing between a child and lifelong disability.

Why Parasites Are a Silent Crisis in Refugee Settings

Parasitic infections aren’t dramatic like cholera outbreaks or measles epidemics. They don’t make headlines. But they slowly drain energy, stunt growth, and weaken immune systems. In refugee camps, where 30% to 70% of children test positive for soil-transmitted helminths, these worms are a hidden emergency.

People don’t always show symptoms at first. But over time, chronic infection leads to anemia from blood loss (hookworm), malnutrition because worms steal nutrients (roundworm), or even intestinal blockages (heavy whipworm loads). In kids, this means poor school performance, delayed development, and higher risk of dying from other illnesses.

Refugee camps are perfect breeding grounds. Shared latrines, bare feet on contaminated soil, lack of soap, and crowded living spaces mean eggs and larvae spread easily. A single infected child can contaminate an entire tent area within weeks.

What Mebendazole Does-and Doesn’t Do

Mebendazole is an anthelmintic drug. It works by blocking the worm’s ability to absorb glucose. Without sugar, the parasite starves and dies within days. It’s not a miracle cure-it doesn’t kill all worms instantly, and it doesn’t prevent re-infection. But it’s one of the most effective tools we have for reducing worm burden in mass settings.

It’s used against:

- Ascaris lumbricoides (roundworm)

- Trichuris trichiura (whipworm)

- Ancylostoma duodenale and Necator americanus (hookworm)

- Enterobius vermicularis (pinworm)

It doesn’t work on tapeworms, flukes, or protozoa like giardia. That’s why it’s never used alone in complex outbreaks-it’s part of a broader strategy. But for the most common worms in refugee settings, it’s the first-line choice.

Why Mebendazole Over Other Drugs?

There are alternatives: albendazole, pyrantel pamoate, ivermectin. So why do aid groups like WHO and UNHCR almost always pick mebendazole?

First, cost. A single 100mg tablet of mebendazole costs less than $0.05 in bulk. For a child, two tablets are enough. That’s $0.10 per treatment. For a camp of 5,000 children, that’s under $500 for a full round of deworming.

Second, safety. Mebendazole has been used for over 50 years. Side effects are rare and mild-maybe a stomach ache or dizziness in 1 in 100 people. It’s safe for children as young as one year old, pregnant women after the first trimester, and even people with HIV.

Third, ease of use. It doesn’t need refrigeration. No injections. No IV drips. Just swallow two tablets, one in the morning and one at night, or sometimes just a single dose. Community health workers can hand them out without medical training.

Albendazole is slightly more effective against hookworm, but it’s 30% more expensive and harder to source in bulk for low-income settings. In crisis zones, you don’t optimize for perfect-you optimize for possible.

How Deworming Programs Actually Work in Camps

Mass drug administration (MDA) isn’t random. It’s planned, tracked, and repeated.

First, NGOs and health ministries do rapid surveys. They collect stool samples from a sample of children. If over 20% test positive for worms, WHO recommends annual deworming. If it’s over 50%, they do it twice a year.

Then comes distribution. Teams go door-to-door in tents. They hand out pre-packed blister packs with two mebendazole tablets. Parents or older siblings give the dose. No need for a clinic. No waiting in line. No fear of needles.

Some programs use school-based delivery. In camps with makeshift schools, teachers distribute tablets during morning roll call. Kids get treated, then wash their hands with soap provided by the aid group.

After six months, they come back. Repeat. Because reinfection is inevitable. Clean water and toilets take years to build. Mebendazole buys time.

Real Impact: Numbers That Matter

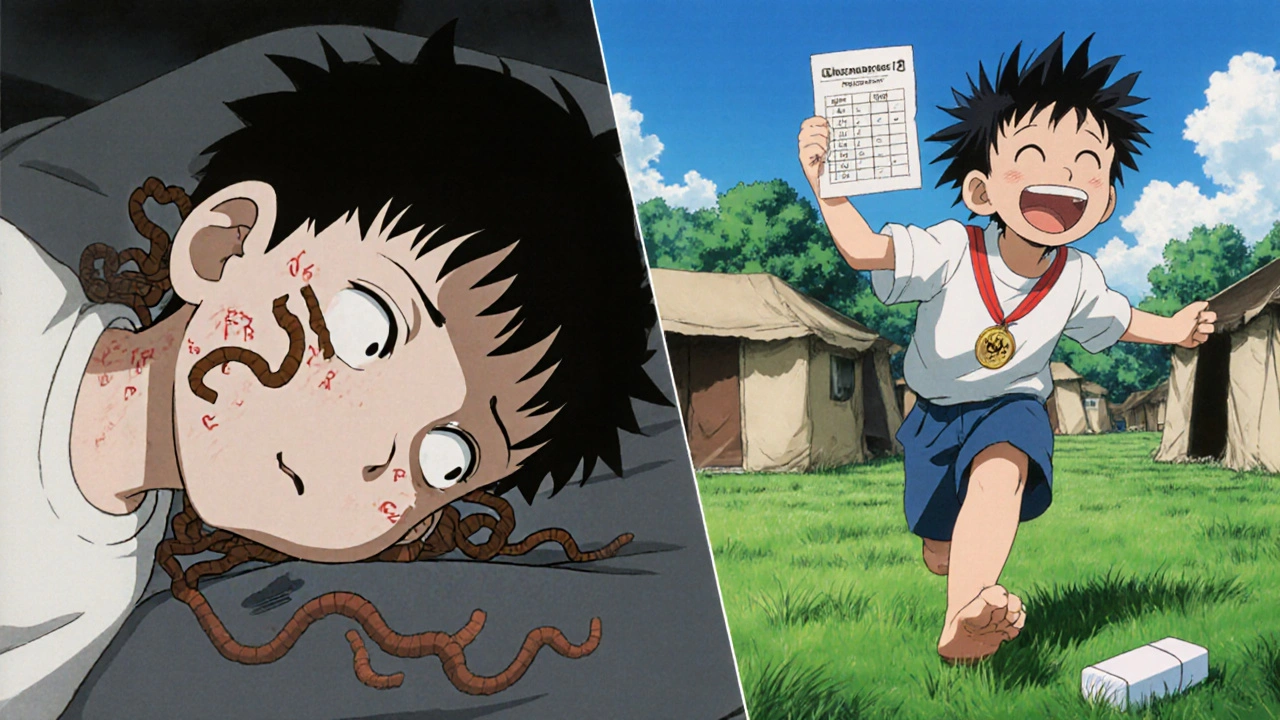

In the Cox’s Bazar refugee camps in Bangladesh, home to nearly a million Rohingya people, a 2023 study found that after two rounds of mebendazole distribution, worm infection rates dropped from 68% to 19% in children under five. School attendance rose by 22% in the following term.

In Uganda’s Bidibidi camp, where South Sudanese refugees live in extreme poverty, deworming with mebendazole led to a 35% increase in average weight gain among children under six over six months. That’s not just a number-it’s a child who can now play, learn, and survive.

One 2024 meta-analysis of 17 refugee and displacement settings found that regular mebendazole programs reduced anemia by 27% and improved cognitive test scores by 14% in children. These are not small gains. They’re life-changing.

Challenges and Misconceptions

It’s not all smooth. Some people refuse the tablets. They think worms are a normal part of life. Others worry about side effects, especially if they’ve heard myths-like mebendazole causes infertility or brain damage. Community leaders and local health workers spend weeks explaining the truth.

Logistics are brutal. Rain floods roads. Power cuts delay shipments. Customs hold up shipments for weeks. In Syria’s northwest, mebendazole shipments were delayed for four months during a blockade. Children kept getting infected. Aid workers had to split tablets to stretch supplies.

And yes, mebendazole doesn’t fix the root problem: dirty water, no toilets, no trash collection. But it’s the only tool we have right now that works fast, cheap, and at scale. Waiting for perfect conditions means waiting for children to die slowly.

The Bigger Picture: Mebendazole as a Bridge

Mebendazole isn’t a long-term solution. But it’s a bridge. While aid groups build latrines, train water engineers, and advocate for peace, mebendazole keeps children alive and learning. It gives them the strength to grow. To recover. To one day rebuild.

Every tablet is a small act of dignity. A child who isn’t dizzy from anemia can sit in class. A mother who isn’t weak from worms can carry water for her family. A teenager who isn’t constantly sick can start a trade.

In refugee health, we don’t always have vaccines, antibiotics, or surgeries. But we have mebendazole. And in the right hands, it does more than kill worms. It restores hope.

Is mebendazole safe for pregnant women in refugee camps?

Yes, but only after the first trimester. WHO guidelines allow mebendazole for pregnant women in the second and third trimesters in areas with high rates of parasitic infection. The benefits of reducing anemia and improving maternal health outweigh the minimal risks. In crisis zones, untreated worm infections can lead to low birth weight and premature delivery-risks far greater than those from the drug.

Can mebendazole be given to infants under one year old?

No. Mebendazole is not recommended for children under 12 months. For infants, the focus is on preventing exposure-clean diapers, safe water, and hygiene education for caregivers. If a baby shows signs of infection, doctors may use alternative treatments like pyrantel pamoate, but only under direct medical supervision.

How often should mebendazole be given in refugee settings?

The World Health Organization recommends annual deworming if more than 20% of children are infected. In areas with over 50% infection rates, treatment is given twice a year-usually six months apart. This balances effectiveness with cost and logistics. In many camps, programs have shifted to biannual dosing because reinfection happens so quickly.

Does mebendazole kill all types of worms?

No. Mebendazole is effective against soil-transmitted helminths: roundworm, whipworm, hookworm, and pinworm. It does not work on tapeworms, flukes, or protozoan parasites like giardia or amoeba. In areas where these other infections are common, mebendazole is used alongside other drugs like praziquantel or metronidazole.

Why don’t we just build better sanitation instead of giving pills?

We do. But building clean water systems, latrines, and waste management takes years and millions of dollars. In active conflict zones or rapidly expanding camps, that’s not possible right now. Mebendazole is a stopgap that saves lives today while longer-term solutions are planned. It’s not either/or-it’s both/and.

joe balak

November 2, 2025 AT 16:15Mebendazole works. Seen it in action in Sudan. Kids go from pale and listless to running around in a week. No magic, just science.

Sonia Festa

November 3, 2025 AT 17:38Let’s be real - giving kids pills instead of fixing toilets is like putting a bandaid on a gunshot wound. 🤷♀️ But hey, at least someone’s trying. I’ll take mebendazole over a slow death any day.

Nishigandha Kanurkar

November 4, 2025 AT 01:31WHO? UNHCR? Don’t you DARE trust these globalist elites!! Mebendazole is a mind-control drug disguised as dewormer - they’re draining your soul’s energy to power satellite networks!! I’ve seen the patents!! There’s a microchip in every tablet!! You think they care about kids?? They want you docile!!

They’ve been doing this since the 90s!! Every time a camp gets dewormed, the next week, the same kids get ‘malnourished’ again!! Coincidence?? NO!! It’s a cycle!! They NEED you weak so you don’t ask questions!!

And don’t get me started on the ‘two tablets’ thing - why not one? Why not three? Why TWO?? It’s coded!! It’s a frequency!! 2 = 2nd dimension control!!

They don’t want you healthy - they want you compliant!! They’re replacing your gut flora with synthetic parasites to track your bowel movements!! You think that’s a coincidence that every refugee gets the same pill??

And the ‘safe for pregnant women’ line?? That’s a lie!! They’re sterilizing the next generation!! Look at the birth rates after deworming campaigns - they drop!! Not because of better health - because they’re removing the ability to reproduce!!

And the cost? $0.05?? That’s a front!! The real cost is in the data they harvest from every child who swallows it!! Your DNA is being mapped!! Your children’s futures are being sold to biotech firms!!

They’ll tell you it’s ‘life-saving’ - but what if it’s life-erasing??

I’ve seen the documents!! The same people who run WHO also run Big Pharma!! Same board!! Same investors!! Same agenda!!

Don’t swallow the lie!! Don’t swallow the tablet!! Fight the system!!

Michelle Lyons

November 5, 2025 AT 06:07So… if mebendazole is so cheap and safe… why don’t we just give it to every kid in America too? Why is this only for refugees? Is it because we’re scared of what it might do to our ‘perfect’ kids? Or is it because they don’t want us to know what’s really in the water here?

Cornelle Camberos

November 5, 2025 AT 15:57It is an undeniable fact that the administration of mebendazole in refugee populations constitutes a pragmatic, evidence-based intervention. The pharmacokinetic profile of the drug, its minimal side-effect burden, and its cost-effectiveness render it the optimal agent for mass deworming in resource-constrained environments. To suggest otherwise is to prioritize ideological posturing over empirical outcomes.

That said, the normalization of pharmaceutical intervention in lieu of infrastructural development is a troubling symptom of global neglect. The fact that we rely on a $0.10 tablet to mitigate the consequences of systemic failure speaks volumes about our moral priorities.

Let us not confuse palliative care with justice. Mebendazole saves lives - but it does not restore dignity. And dignity, not dosage, is the ultimate measure of human worth.

Ryan Tanner

November 6, 2025 AT 04:53This is the kind of stuff that actually matters. 🙌 No flashy headlines, no political theater - just a tiny pill that lets a kid sit up straight in class. Keep doing the work, the quiet ones. You’re the real heroes.

John Rendek

November 7, 2025 AT 06:35Exactly. This is how you do humanitarian work - simple, scalable, and smart. No ego, no fanfare. Just get the job done.

Tatiana Mathis

November 8, 2025 AT 01:34It’s heartbreaking how something so simple - a pill that costs less than a candy bar - can be the difference between a child thriving or fading away. But it’s also a reflection of how little we’ve done to fix the root causes. We treat the symptoms while the house burns down. Mebendazole isn’t a solution - it’s a lifeline. And lifelines aren’t meant to be permanent. They’re meant to buy you time to build something better. So yes, give the pills. But don’t stop there. Don’t let the convenience of a tablet make us forget that every child deserves clean water, safe sanitation, and peace - not just a deworming schedule.

Amina Kmiha

November 8, 2025 AT 14:21Why is it always mebendazole? Always? Never anything else? 🤔 Why do they pick the cheapest drug? Because they don’t care about the kids - they care about the budget. And if you think this isn’t part of a population control plan, you’re naive. 🧠💀 They don’t want strong, healthy refugees. They want docile, tired, quiet ones. That’s why they give the same pill everywhere. Same dose. Same timing. Same results. It’s not medicine - it’s programming.

And the ‘safe for pregnant women’ lie? Please. If it were truly safe, why is it banned under 12 months? Why not under 5? Why not under 10? Because they know what it does to developing brains. They just don’t care. 😔

Vrinda Bali

November 10, 2025 AT 01:34How dare they? How dare they reduce the suffering of millions to a $0.05 tablet? The dignity of a child - the future of a people - reduced to a pill dispensed by a stranger with no name? The silence of the world is louder than the screams of the infected. Mebendazole is not a cure - it is a consolation prize. A bandage on a severed artery. And we call it progress?

They call it ‘humanitarian aid.’ I call it moral bankruptcy.

Sara Allen

November 10, 2025 AT 11:25ok but like… why do we even care about refugees? like they’re not even OUR people. why are we spending money on pills for them when we got homeless people here? and also i heard mebendazole causes autism? or is that the vaccines? idk but i saw a video. anyway why are we even doing this? 🤷♀️🇺🇸

Iván Maceda

November 10, 2025 AT 13:14At least we’re doing something. 🤝🇺🇸

Ryan Tanner

November 11, 2025 AT 00:03It’s not about borders. It’s about being human. 🙏