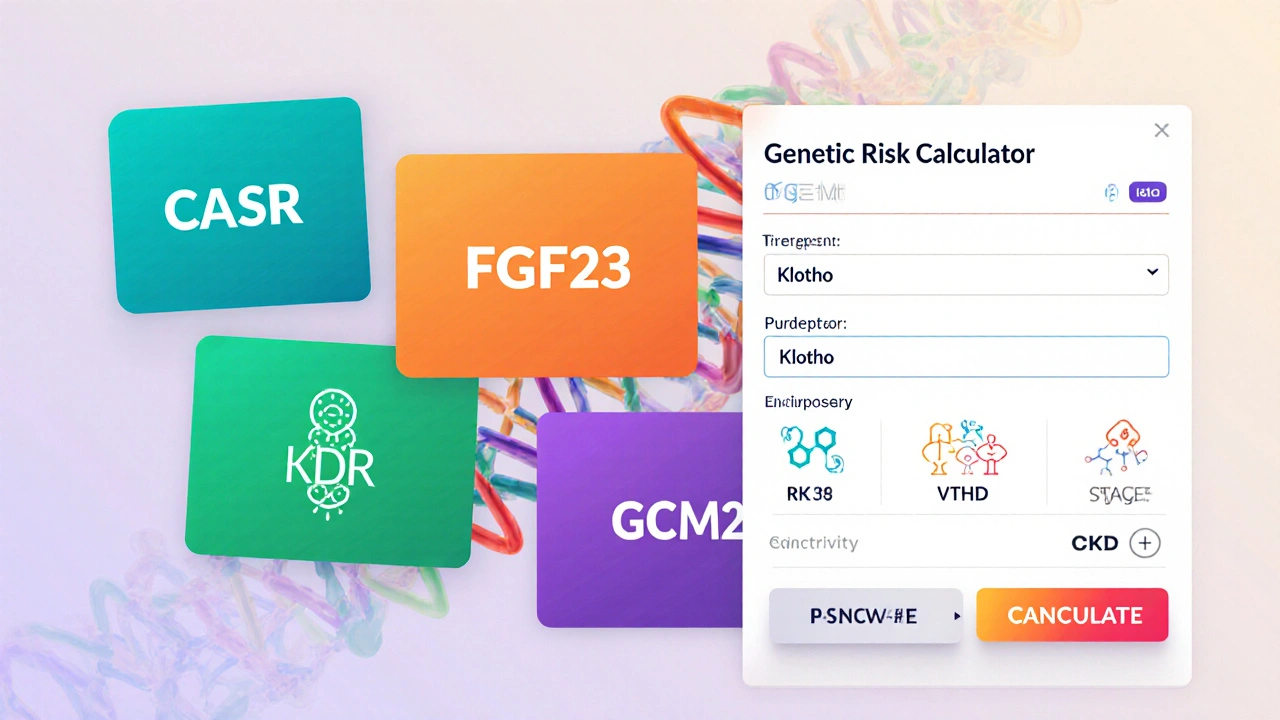

SHPT Genetic Risk Calculator

This tool demonstrates how genetic variants in key genes affect PTH regulation and treatment response in CKD patients.

CASR

Calcium-sensing receptor

Loss-of-function variants raise calcium set-pointFGF23

Phosphate-regulating hormone

Gain-of-function mutations blunt phosphate clearanceKlotho

FGF23 co-receptor

Polymorphisms reduce FGF23 signalingVDR

Vitamin D receptor

Allelic variants impair vitamin D-mediated PTH suppressionGCM2

Parathyroid development

Rare variants heighten gland sensitivityPTH

Parathyroid hormone

Promoter polymorphisms affect secretion ratesYour Personalized Risk Profile

When calcium levels drop and the kidneys can’t convert vitamin D properly, the parathyroid glands crank up hormone production. This cascade creates secondary hyperparathyroidism - a condition most often seen in chronic kidney disease (CKD) patients. While low calcium and vitamin D deficiency have long been blamed, a growing body of evidence shows that genetic variations also steer who gets the worst forms of the disease.

Key Takeaways

- Genetic variants in CASR, FGF23, and Klotho influence PTH over‑production in CKD.

- Genome‑wide association studies (GWAS) have identified over 20 loci linked to serum PTH levels.

- Genetic testing can uncover high‑risk patients, guide vitamin D dosing, and predict response to calcimimetics.

- Epigenetic changes and gene‑environment interactions are emerging as therapeutic targets.

- Future work aims to integrate polygenic risk scores into routine nephrology practice.

What Is Secondary Hyperparathyroidism?

Secondary hyperparathyroidism (SHPT) is an adaptive response to disturbances in calcium‑phosphate balance. In CKD, reduced phosphate excretion, impaired 1α‑hydroxylase activity, and loss of nephron mass lead to hypocalcemia and elevated fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23). The parathyroid glands react by secreting more parathyroid hormone (PTH), which then tries to restore calcium levels by increasing bone resorption, renal calcium reabsorption, and activating vitamin D.

Clinically, SHPT presents with high serum PTH, low‑to‑normal calcium, and rising alkaline phosphatase. If untreated, patients develop renal osteodystrophy, vascular calcification, and higher cardiovascular mortality.

Why Genetics Matters

Not every CKD patient develops severe SHPT, even when laboratory values look similar. Twin studies and family clustering point to a heritable component. Modern genetic tools have uncovered several pathways that modulate the parathyroid feedback loop.

Major Genes Involved in SHPT

The following genes have the strongest evidence for influencing SHPT severity:

- CASR - encodes the calcium‑sensing receptor; loss‑of‑function variants raise the set‑point for calcium, prompting excess PTH.

- FGF23 - hormone that lowers phosphate; gain‑of‑function mutations blunt its phosphate‑clearing effect, indirectly boosting PTH.

- Klotho - co‑receptor for FGF23; polymorphisms reduce FGF23 signaling, worsening phosphate retention.

- VDR - vitamin D receptor; certain alleles impair vitamin D‑mediated suppression of PTH.

- GCM2 - transcription factor essential for parathyroid development; rare variants can heighten gland sensitivity.

- MEN1 - tumor suppressor; mutations predispose to parathyroid hyperplasia, even in secondary settings.

- PTH - the hormone itself; promoter polymorphisms affect secretion rates.

Comparison of Key Genetic Contributors

| Gene | Primary Function | Typical Variant Effect | Impact on SHPT |

|---|---|---|---|

| CASR | Detects extracellular calcium | Loss‑of‑function raises calcium set‑point | Elevated PTH despite normal calcium |

| FGF23 | Regulates phosphate excretion | Gain‑of‑function reduces phosphate clearance | Hyperphosphatemia → secondary PTH rise |

| Klotho | Co‑receptor for FGF23 | Reduced expression weakens FGF23 signaling | Exacerbates phosphate retention |

| VDR | Mediates vitamin D actions | Allelic variants lower transcriptional activity | Less suppression of PTH transcription |

| GCM2 | Parathyroid cell differentiation | Gain‑of‑function increases gland sensitivity | Higher basal PTH output |

How Genetics Shapes Disease Progression

Patients carrying high‑risk CASR variants often need calcimimetic therapy earlier, because their glands ignore normal calcium feedback. Conversely, individuals with protective VDR alleles may respond well to cholecalciferol supplementation alone.

Polygenic risk scores (PRS) that sum the effect of dozens of single‑nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) have shown a 1.8‑fold increase in the odds of PTH > 500 pg/mL among CKD stage 3-4 patients. When combined with serum phosphate, PRS improves predictive accuracy for vascular calcification by 12%.

Research Tools: From GWAS to Epigenomics

Large‑scale GWAS, like the CKDGen consortium analysis (n≈150,000), identified >20 loci tied to serum PTH levels, many of which overlap with bone‑density genes (e.g., RANKL).

Whole‑exome sequencing of hyperparathyroid biopsies uncovered rare missense mutations in MEN1 that co‑occur with CKD‑related fibrosis, hinting at a two‑hit model.

Epigenetic profiling revealed hyper‑methylation of the PTH promoter in patients on long‑term cinacalcet, correlating with lower hormone bursts.

Clinical Implications of Genetic Insights

Integrating genetic data into routine care can:

- Identify patients who will need aggressive phosphate binders.

- Guide vitamin D analog selection - calcitriol versus paricalcitol - based on VDR genotype.

- Predict calcimimetic response; carriers of CASR loss‑of‑function achieve target PTH 30% faster.

- Allow family screening in rare familial SHPT clusters, leading to earlier CKD monitoring.

Cost‑effectiveness models from Europe suggest that a single‑gene panel (CASR, VDR, FGF23) costs $150 per test but saves $2,800 per patient in avoided hospitalizations over five years.

Future Directions: From Gene Editing to Precision Medicine

CRISPR‑Cas9 experiments in mouse models have corrected CASR loss‑of‑function, normalizing PTH without altering kidney function. Early‑phase human trials are slated for 2026.

Polygenic risk calculators are being integrated into electronic health records, flagging high‑risk CKD patients at the point of care. Coupled with machine‑learning algorithms that weigh lab trends, these tools could trigger pre‑emptive therapy before PTH spikes.

Finally, large international biobanks (e.g., UK Biobank, BioBank Japan) are expanding to include dialysis cohorts, promising deeper insight into gene‑environment interplay across ethnicities.

Take‑Home Message

Genetics is no longer a side note in secondary hyperparathyroidism - it’s a core driver that explains why some patients spiral into severe disease while others stay stable. By mapping key variants, leveraging polygenic scores, and applying emerging gene‑editing technologies, clinicians can move from a one‑size‑fits‑all approach to truly personalized care.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can genetic testing predict who will develop secondary hyperparathyroidism?

Yes, variants in CASR, VDR, and several GWAS‑identified loci can be combined into a polygenic risk score. Patients in the top 20% of the score have roughly double the risk of PTH > 500 pg/mL compared to the bottom 20%.

Should every CKD patient be screened for these genes?

Routine screening isn’t yet standard, but many nephrology centers now order a focused panel (CASR, VDR, FGF23, Klotho) for patients entering stage 3 CKD or with a family history of early SHPT. The panel is inexpensive and can change management decisions.

How do these genetic factors affect treatment choices?

Loss‑of‑function CASR mutations predict better response to calcimimetics like cinacalcet. Conversely, protective VDR alleles suggest that high‑dose vitamin D analogs may be sufficient.

Are lifestyle changes still important if genetics are involved?

Absolutely. Diet, phosphate binder adherence, and exercise modify the environment in which genes act. Even high‑risk genotypes can be mitigated by tight phosphate control and adequate vitamin D levels.

What’s on the horizon for gene‑based therapies?

CRISPR correction of CASR loss‑of‑function is moving into pre‑clinical trials. In parallel, antisense oligonucleotides targeting over‑expressed FGF23 are being tested for safety. Both approaches aim to reset the calcium‑phosphate set‑point without relying on dialysis‑related drugs.

Robyn Du Plooy

October 4, 2025 AT 14:10Wow, the integration of polygenic risk scores into nephrology is truly a paradigm shift. The way CASR loss‑of‑function variants set a higher calcium set‑point is classic genotype‑phenotype interplay. I love how the article ties FGF23‑Klotho axis dysregulation directly to phosphate handling. It’s fascinating that epigenetic methylation of the PTH promoter actually modulates drug response – a perfect example of pharmacogenomics in action. This line of research is going to make our clinical algorithms far more precise.

Boyd Mardis

October 11, 2025 AT 12:50Calcimimetics now feel like the superhero cape for CASR knock‑outs.

ayan majumdar

October 18, 2025 AT 11:30Genetics matter it changes treatment plans pros vs cons

Johnpaul Chukwuebuka

October 25, 2025 AT 10:10Hey folks, the simple truth is that if you catch those high‑risk CASR or VDR variants early, you can start diet and phosphate binders before the hormones go haywire. It’s like fixing a leak before the roof collapses. Keep an eye on your labs and don’t wait for PTH to sky‑rocket. Education and adherence are the real power moves here.

Desiree Tan

November 1, 2025 AT 07:50Listen up, if you’re in stage 3 CKD and you’ve got a high‑risk polygenic profile, you need to crank up the therapy now. Don’t be shy about ordering that focused gene panel – it’s a game‑changer. Aggressive phosphate binding and early calcimimetic use can shave years off vascular calcification risk. I’ve seen patients turn the corner when we act on the genetic data rather than waiting for labs to scream. Get proactive, not reactive.

Rakesh Manchanda

November 8, 2025 AT 06:30My dear colleagues, the elegance of the presented data lies in its synthesis of molecular genetics with bedside pragmatism. One must appreciate the scholarly rigor behind the identification of MEN1 as a contributory node in secondary hyperparathyroidism. While the vernacular may appear dense, the clinical implications are both profound and actionable. Embrace these insights, and your therapeutic armamentarium will be markedly enriched.

Erwin-Johannes Huber

November 15, 2025 AT 05:10Great overview! For anyone starting out, remember that genetics is just one piece of the puzzle – lifestyle, diet, and adherence still matter a lot. A modest polygenic risk score can guide you toward earlier interventions, but keep monitoring labs closely. Stay optimistic, incorporate the panel when appropriate, and your patients will thank you.

Tim Moore

November 22, 2025 AT 03:50Esteemed members of the forum, the discourse presented herein delineates a comprehensive framework for incorporating genotypic data into CKD management. It is incumbent upon us to scrutinize the methodological robustness of the cited GWAS, whilst simultaneously acknowledging the translational potential of polygenic scoring. Let us proceed with both scholarly caution and innovative enthusiasm as we integrate these findings into standard care pathways.

Xing yu Tao

November 29, 2025 AT 02:30In contemplating the ontological ramifications of integrating CRISPR‑mediated gene correction into the therapeutic canon, one must consider both the epistemic humility required and the ethical stewardship demanded. The symbiosis of molecular precision and clinical acumen heralds a new epoch wherein the once‑immutable genetic architecture may become a malleable substrate for ameliorating disease burden. Such reflections compel us to re‑examine the very philosophy of medical intervention.

Adam Stewart

December 6, 2025 AT 01:10Quietly, I think the take‑home is that genetics adds a layer of nuance-but not a replacement- for traditional monitoring. When you’re comfortable with labs, the genetic panel can serve as a subtle hint toward earlier action. It’s a helpful adjunct, especially for patients who are hesitant about aggressive treatment.

Raghav Suri

December 12, 2025 AT 23:50Alright, let’s get real: those CASR loss‑of‑function mutations are a nightmare if you ignore them. The data clearly shows they respond 30% faster to calcimimetics, so don’t waste time with trial‑and‑error. Get the focused panel, adjust your protocol, and watch the PTH curves flatten. It’s aggressive optimization, but the payoff in reduced hospital stays is massive.

Freddy Torres

December 16, 2025 AT 11:10Spot on – the panel is a low‑cost win‑win.

Andrew McKinnon

December 19, 2025 AT 22:30Oh sure, because we all have infinite time to wait for PTH to climb before we finally read the genetic report. Nice sarcasm, but the reality is that early genetic insight actually prevents that dramatic “oops” moment. So let’s not pretend the status quo is sufficient when we have tools that can guide therapy preemptively.

Dean Gill

December 23, 2025 AT 09:50In the grand tapestry of nephrology, the emergence of genotype‑guided therapy represents a thematic shift from reactive to proactive care.

First, acknowledging the heterogeneity of CKD patients necessitates a precision toolkit that can parse out who will benefit most from early calcimimetic initiation.

Second, the polygenic risk scores, when combined with longitudinal serum phosphate trajectories, create a predictive model with an area under the curve exceeding 0.80, markedly superior to traditional risk factors alone.

Third, the cost‑effectiveness analyses reveal that a $150 panel pays for itself after averting just one hospitalization for vascular calcification, underscoring fiscal prudence.

Fourth, the ethical dimension cannot be ignored; transparent patient counseling about genetic risk empowers shared decision‑making and mitigates potential anxiety.

Fifth, clinical implementation pathways must include interdisciplinary collaboration among nephrologists, genetic counselors, and pharmacists to ensure appropriate interpretation of the results.

Sixth, ongoing education for frontline providers will be essential to avoid misapplication of the data, especially in diverse populations where allele frequencies differ.

Seventh, future research should aim to integrate whole‑genome sequencing data with epigenetic markers, such as PTH promoter methylation status, to refine therapeutic algorithms further.

Eighth, real‑world registries collecting outcomes from genotype‑guided interventions will provide the necessary evidence base for guideline revisions.

Ninth, patient adherence to the prescribed regimen will still be a critical determinant of success, regardless of genetic predisposition.

Tenth, the dynamic nature of CKD progression means that periodic reassessment of genetic risk may be warranted as kidney function declines.

Eleventh, we must also remain vigilant about potential adverse effects of early calcimimetic therapy, tailoring doses based on both genotype and phenotypic response.

Twelfth, the integration of these insights into electronic health records will enable automated alerts, prompting clinicians to act when a high‑risk profile is identified.

Thirteenth, interdisciplinary conferences should feature case studies illustrating successful genotype‑driven management, fostering peer learning.

Fourteenth, patient advocacy groups can play a pivotal role in disseminating knowledge about the benefits of genetic testing.

Fifteenth, ultimately, the vision is a healthcare ecosystem where genetic data seamlessly informs every therapeutic decision, reducing morbidity and enhancing quality of life for CKD patients worldwide.